PFAS in the Potomac River Basin

Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin

The following information was compiled by the Water Quality Workgroup for the Potomac River Basin Drinking Water Source Protection Partnership (DWSPP). It provides background and current information for PFAS in the Potomac River basin, including a review of federal regulations and the regulatory status in each state in the basin—Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

What are PFAS

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a complex family of man-made fluorinated organic chemicals that have been on the market since the 1930s. What makes these compounds unique are their physical and chemical properties, which include oil and water repellency, temperature resistance, and friction reduction. These properties have made PFAS an ideal component for coatings in textiles, paper products, and cookware. PFAS are also used in firefighting foams, aerospace, photographic imaging, semiconductor, automotive, construction, electronics, and aviation industries.

They are called “forever chemicals” because the carbon–fluorine bonds in these compounds are hard to break. The longer the chain, the harder it is to break the bonds. Based on the length of the carbon chain, the PFAS compounds are broadly classified as long-chain and short-chain compounds. PFAS compounds can vary in length between 4 and 12 molecules. “Long-chain” PFAS compounds are typically defined as having 6 or more carbons while “short-chain” compounds usually have 7 carbons or less, depending on the chemical make-up. There is an overlap of 6-8 carbons between long- and short-chain PFAS compounds, depending on the presence of carboxylic (up to 7 carbons short chain; greater than 7 carbons long chain) and sulfonic acids (up to 5 carbons short chain; greater than 5 carbons long chain).

The scientific community has been studying and understanding the environmental and health impacts associated with PFAS compounds for some time now. EPA’s PFAS webpage provides a summary of the environmental and human risks associated with PFAS compounds.

Sampling for PFAS in the Potomac Watershed

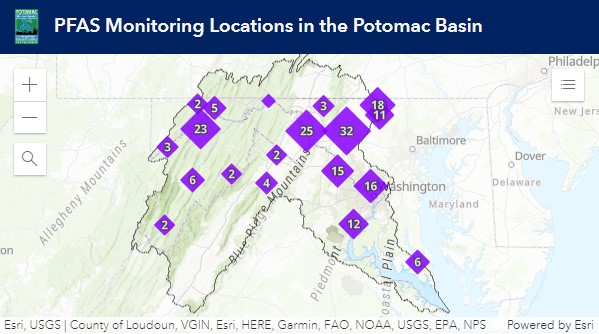

The DWSPP created a map that showcases PFAS monitoring in the Potomac River Basin.

Various agencies are conducting sampling across the Potomac watershed for PFAS. The publicly available data in the interactive map below was compiled by members of the Potomac River Basing Drinking Water Source Protection Partnership.

Please note, the map is not meant to be a comprehensive list of PFAS monitoring in the Potomac River Basin. Please contact the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin if you have questions about the map.

Federal PFAS Regulations

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was first alerted to the risks from these compounds in 1998. Although some PFAS have been manufactured for more than 50 years, PFAS were not widely documented in environmental samples until the early 2000s.

U.S. manufacturers voluntarily phased out production and use of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) in 2002. In 2006, EPA invited eight leading manufacturers to join the Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Stewardship program (under the Toxic Substances Control Act—TSCA) to work towards voluntary elimination of these products from manufacturing by 2015. According to an EPA announcement from July of 2021, the program continues for other PFAS compounds.

In 2019, EPA put forward the PFAS Action Plan in an effort to understand PFAS and reduce the risk from these compounds to the public. This effort implements the steps laid out in the plan and through active engagement and partnership with other federal agencies, states, tribes, industry groups, associations, local communities, and the public. As part of its Action Plan implementation, EPA proposed regulatory determinations for PFOS and PFOA in drinking water in 2020. In 2021, EPA put forward the PFAS Strategic Roadmap which outlined EPA’s path forward in addressing PFAS. According to EPA, “the roadmap sets timelines to take specific actions and commits to bolder new policies to safeguard public health, protect the environment, and hold polluters accountable.”

EPA has rolled out new PFAS Analytic Tools under its Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) that consolidates PFAS data from 11 different databases in one searchable web-based platform. The goal is to make the data more accessible to the public, researchers, and other stakeholders.

Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA)

In 2009, EPA developed Provisional Health Advisory values for PFOA (0.4 µg/L) and PFOS (0.2 µg/L) to assess potential risk from exposure to these chemicals through drinking water. In 2016, EPA established the combined health advisory for PFOA and PFOS at 70 ng/L or parts per trillion (ppt).

The 1996 SDWA amendments require that every five years EPA issue a new list of unregulated contaminants to be monitored by public water systems. This data supports the agency’s efforts to regulate particular contaminants of potential public health concern. PFAS monitoring first appeared on the list in UCMR3. The data summary from UCMR3 did not lead to PFAS regulations. Consistent with recent statutory changes, including the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020, EPA is committed to monitoring for PFAS in the upcoming Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule 5 (UCMR5) cycle. Data collection will begin in 2023 under the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR5) for 29 different PFAS compounds across public water systems serving large and small populations.

In 2022, EPA announced interim updated drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS, GenX and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) that replace those EPA issued in 2016 under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). On March 14, 2023, EPA published the proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR). The regulation is expected to be finalized after the comment period which is 60 days after publication in the Federal Register. A fact sheet on EPA’s Proposal to Limit PFAS in Drinking Water is available.

Clean Drinking Water (CWA)

In 2022, EPA released a memorandum to states, about the use of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to protect against PFAS compounds. The guidance outlines three steps that can be taken towards this goal. This memorandum seeks to align wastewater and stormwater NPDES permits and pretreatment program implementation activities with the goals in EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap.

EPA also continues to focus on limiting PFAS discharges from multiple industrial categories, as outlined in the 2021 PFAS Strategic Roadmap. The Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15 provides information on the steps taken by EPA. A 2023 EPA press release discussed a new study to develop technology-based pollution limits and studies on wastewater discharges from industrial sources.

The top priority of EPA’s Biosolids Program is to assess the potential human health and environmental risk posed by pollutants found in biosolids. EPA will complete the risk assessment for PFOA and PFOS in biosolids by December 2024.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA)

Prompted by a petition from the Governor of New Mexico, to list PFAs as hazardous waste, in October 2021, EPA announced important steps toward evaluating the existing data for four PFAS compounds (PFOA, PFOS, PFBS and GenX) under the RCRA and strengthening the ability to clean up PFAS contamination across the country through the RCRA corrective action process.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA)

In 2022, EPA proposed to designate PFAS, PFOA, and PFOS, including their salts and structural isomers, as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as Superfund. This proposed rulemaking would increase transparency around releases of these harmful chemicals and help to hold polluters accountable for cleaning up their contamination. Any entity in charge of a vessel or a facility must notify the National Response Center whenever there is a release of either chemical of greater than the reportable quantity, which is one pound over a 24-hour period. EPA noted that one pound is the default reportable quantity for all listed hazardous substances; the reportable quantity for PFOA and PFOS may be changed in the future, but any change would be subject to further notice-and-comment rulemaking. Also, whenever federal agencies sell or transfer federally owned real property, they must provide notice if either chemical was stored there for more than one year or was disposed of or released at the property. The listing of PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances requires the Department of Transportation to list and regulate the substances. EPA plans to finalize this rule in 2023.

Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)

In December 2022, EPA proposed revisions to the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) reporting by notice in the Federal Register. Among the changes would be to include PFAS as Chemicals of Special Concern and eliminate the de minimis exemption previously relied upon to avoid reporting.

Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)

The TSCA of 1976 provides EPA with authority to require reporting, record-keeping and testing requirements, and restrictions relating to chemical substances and/or mixtures. Under TSCA, EPA proposed two new guidance documents with suggestions for incorporating PFAS monitoring—and related conditions—in permits issued under the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). The first guidance document, issued April 28, 2022, describes EPA’s approach where it is the permit issuer or pretreatment control authority. This was followed by a second guidance document issued December 5, 2022, for guidance where states delegated under the Clean Water Act (CWA) are the permit issuers. These supersede the November 2020 Interim Strategy for EPA-issued NPDES Permits. EPA now recommends use of draft analytical method 1633 to detect PFAS in discharges even though it hasn’t yet been approved under 40 C.F.R. Part 136. PFAS monitoring has already been incorporated into certain industrial discharge permits issued in Massachusetts.

State PFAS Regulations

The jurisdictions in the Potomac River basin are addressing PFAS through regulations. The various approaches are included below.

Virginia PFAS Regulations

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality has compiled an online dashboard with PFAS detection and concentration. It includes results from surface water, fish tissue, and sediment testing.

In 2020, HB 586 was passed, which required the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) to convene a work group to study the occurrence of PFOA, PFOS, perfluorobutyrate (PFBA), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), and other perfluoroalkyl and PFAS. The work group was tasked with developing recommendations for specific maximum contaminant levels for these compounds. The work group included representatives of waterworks owners and operators, including owners and operators of community waterworks, private companies that operate waterworks, advocacy groups representing owners and operators of waterworks, consumers of public drinking water, a manufacturer with chemistry experience, and other relevant stakeholders. Workgroup members were asked to conduct PFAS sampling and report results. There were 50 water systems sampled. The report was published in September 2021.

In addition to HB 586, in 2020, HB 1257 was also passed. It directed VDH to adopt regulations establishing maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) in public drinking water systems for PFOA, PFOS, and other perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances as the Board deems necessary.

In 2022, HB 919 directed VDH to continue review of the recommendations of any work group convened to study the occurrence of PFOA, PFOS, and other perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances as the Board deems necessary in public drinking water. They must do so prior to adopting regulations establishing MCLs in all water supplies and waterworks in the Commonwealth.

Maryland PFAS Regulations

In 2020, the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) started sampling 129 public water treatment systems for PFAS. That initial phase of drinking water sampling was completed and a report, Understanding the occurrence of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Maryland’s Public Drinking Water Sources – Phase 1, was issued in July 2021. For the second phase of sampling, drinking water systems were selected based on consumer potential for long-term exposure to PFAS, source water vulnerabilities, interest by MDE in determining whether groundwater from confined aquifers are less likely to be impacted by PFAS, and proximity to potential PFAS sources. The Phase 2 report describes the results of sampling of 65 public water systems across the state. Sampling for the third phase began in August 2021 and was completed in late spring 2022. A report is expected shortly.

When levels higher than EPA’s health advisory levels of 70 ppt were measured, MDE worked with the water systems to ensure that the affected water treatment plants were offline while the needed confirmation samples were collected and issued public notices. The Maryland Department of Health, out of an abundance of caution, has issued a health advisory for a specific PFAS—PFHxS—in drinking water in concentrations at or above 140 ppt. More Information on the Maryland PFAS Strategy can be found on MDE’s PFAS website.

Pennsylvania PFAS Regulations

In 2018, Governor Wolf signed an Executive Order and established a PFAS Action Team to develop a comprehensive response to identify and eliminate sources of contamination, ensure drinking water is safe, manage environmental contamination, review gaps in data and oversight authority, and recommend actions to address those gaps. Under this order a statewide sampling program was devised.

The statewide sampling plan began in June and is expected to take a year to complete. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protections (PADEP) collected and sent the samples to an accredited laboratory to test for six PFAS chemicals: PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFHxS, PFHpA, and PFBS. The PFAS Action Team released an Initial Report in December 2019. The Report includes information about PFAS, challenges associated with managing contamination, actions taken to date, and recommendations for future actions. Recommendations include additional funding for communities dealing with PFAS contamination and strengthened statutory authorities to adequately address PFAS.

Statewide sampling was also carried out for PFAS. In 2020, the sampling program was modified. The sampling method used was EPA Method 537.1 (18 PFAS). All 2019 sampling was repeated for consistency. The second round of sampling was completed in March 2021, with final sample results posted in June 2021. In January 2023, Pennsylvania put forward regulations for PFOA and PFOS. The maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG) for PFOA and PFOS, respectively, were set at 8 ppt and 14 ppt. The maximum contaminant level (MCL) for PFOA and PFAS respectively are set at 14 ppt and 18 ppt. The PADEP provides a summary of Pennsylvania’s PFAS related actions and regulations.

West Virginia PFAS Regulations

A West Virginia PFAS Work Group was convened in 2019, consisting of members from the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP), the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources (WVDHHR), and the United States Geological Service (USGS), with the goal of determining the best path forward for studying PFAS. This collaborative working group meets quarterly to share developing news on these emerging contaminants, discuss PFAS investigation activities in the State, evaluate any recently produced data, and determine State needs and action plans based on these updates (including implementation of federal regulations).

In 2020, the Senate Concurrent Resolution 46 (SCR46) was passed. As per the resolution WVDEP and the WVDHHR, along with USGS initiated a public source-water supply study to sample PFAS for all community water systems. The study concluded in May 2021. The report, Occurrence of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Inorganic Analytes in Groundwater and Surface Water Used

as Sources for Public Water Supply in West Virginia, was published by USGS. In 2021, HB2722 was passed. It amended the Fire Prevention and Control Act, limiting the use of firefighting foam containing PFAS.

The PFAS study conducted was for raw water samples. Currently WVDEP is coordinating with DHHR and the USGS to test for these compounds in finished (drinking) water at all sites identified as having PFOA or PFOS detections in the raw water above the health advisory limits that were put forward by EPA in 2016.