Forests and Water Treatment Costs

Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin

Forest Cover Impacts on Drinking Water Utility Treatment Costs in a Large Watershed

Water utilities across the United States and the world face difficult decisions in evaluating source water protection opportunities. While source water protection is seen as an important component of a multi-barrier approach to providing high-quality drinking water, it can be difficult to assess the financial benefits of specific programs.

A recent study, conducted by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, explored the relationship between forest cover and source water protection. The project, titled Forest Cover Impacts on Drinking Water Utility Treatment Costs in a Large Watershed, applied sophisticated watershed modeling tools to determine the potential impacts of forest loss on water quality (specifically nutrients, sediments, and total organic carbon), and how this in turn may affect drinking water treatment costs. This project provides an initial evaluation of the water quality and potential cost benefits of protecting forested land within the Potomac River basin, but the approach is applicable to any other supplier.

A summary of the findings can be found below. Members of the Water Research Foundation have access to the full report on their website.

The project was generously funded by The Water Research Foundation, the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities, Fairfax Water, DC Water, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers-Washington Aqueduct, and the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC).

Results and Recommendations

One Size Does NOT Fit All

The results of this study indicate that potential reductions in water treatment chemical costs due to forest protection by themselves may not be a sufficient driver for forest protection or installation of forest buffers for the participating utilities, at least over the scale and time frame examined in this study. The study found that the largest decrease in daily treatment chemical dose was 1.63 percent in one of the forest cover change scenarios for WSSC. Changes in water quality conditions near the participating utility’s intakes would only improve between one and five percent under the various scenarios. While these are the results for the three utilities, it would be wrong to conclude that it is never true for any water utility: one recommendation from this study is to resist generalizations.

When reviewing the results of the study a few caveats should be considered:

- Only forest conservation and forested buffers were studied. This is a very narrow aspect of source water protection, which could include agricultural best management practices or low impact development.

- The source water portion of the Potomac Basin is quite large: 11,560 mi2 covering parts of four states. Smaller watersheds might see greater benefits from forest protection.

- Land use change scenarios were only studied out to 2030, the furthest projection possible from the Chesapeake Bay Land Change Model. Also, the maximum modeled loss of forested land was only 2%. Studying more significant forest losses over a longer time frame would likely produce greater estimates of preservation benefits.

- The Potomac Basin is ~50% forested. Watersheds with higher percentage forest are expected to see more significant changes in water quality from changes in forested land use.

- All surface water treatment plants in the area have invested in conventional treatment. Modest increases in total organic carbon and turbidity would increase coagulant costs, but conventional plants can already treat for these contaminants. Marginal changes in treatment inputs are unlikely to indicate much opportunity for cost savings compared with the need for new treatment processes.

A Commitment to our Drinking Water

Despite the results, the water utilities remain committed to protecting the Potomac River basin. Assigning costs to watershed degradation requires better assessment of the impacts of land use and climate changes on recalcitrant parameters like halogen ions and synthetic organics. Filling this knowledge gap, along with better understanding the enormous costs to treat for them across a variety of watersheds, could assist in identifying financial drivers for source water protection.

There are multiple reasons for conserving forests or installing forest buffers, some of which may stem from other interests of the water suppliers. For example, conserving forests in sensitive areas where development would make the likelihood of runoff from a transportation corridor or industrial activity more likely and increase the risk of spills threatening the water supply. There also are reasons that do not directly concern water supply. Forest conservation may be required to preserve local water quality. Forest buffers may result from nutrient trading to reduce the amount of retrofitting in ultra-urban areas to restore water quality in Chesapeake Bay. If reduction of treatment costs or source water protection is insufficient to justify forest preservation, it may be one element among others to provide adequate justification.

In addition to costs from treatment chemicals, infrastructure, solids handling, and implementation, utilities may consider factors that are more difficult to evaluate economically. These could include reducing the risk (and costs) associated with impacts from fire, climate change, pests, population growth (urbanization), and land use and drinking water regulations.

The results of this project indicate a need for a holistic approach to source water protection in the Potomac basin that includes continued dialogue with the numerous stakeholders and upstream and downstream interests.

Please feel free to contact us with any questions or for more information about the report.

The following provides more detailed information on the Forest Cover Impacts on Drinking Water Utility Treatment Costs in a Large Watershed project.

Scope of Work

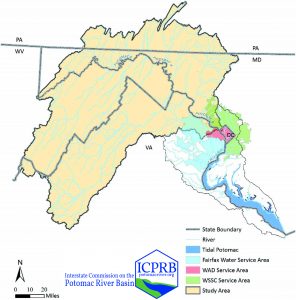

Forested lands comprise about 58 percent of the land cover within the 11,560 square-mile area of the non-tidal Potomac basin–the source water area for the participating utilities. A portion is protected through federal, state, and local management programs or through private conservation easements. Federal land holdings, including the George Washington National Forest in the basin’s headwaters, comprise about 10 percent of the freshwater Potomac watershed.

By 2030, the population of the entire Chesapeake Bay watershed is expected to increase by 13 percent, with much of the growth anticipated in the National Capital Region.

This study evaluated the potential economic benefits of forest protection to these participating water utilities. The study was not intended to be a cost-benefit analysis, but an initial look at changes in cost for select treatment chemicals. Future research would be needed to provide a broader and more complete cost-benefit analysis of operational and capital cost savings as compared to the costs of forest or buffer protection.

Additionally, a case study looked at treatment costs beyond increased chemical addition. It explored solids handling costs and treatment costs for constituents not easily removed by conventional treatment. Solids handling costs were observed to be significant and sensitive to coagulant doses. It was also observed that halogen ions, synthetic organics that are not effectively removed by conventional treatment, would be costliest to treat. Because the costs of treating for these contaminants is so high, it makes sense to focus source water protection efforts on these contaminants. This finding may be very instructive to future watershed research.

Download the full Scope of Work to read more about the phases, methodology, and the original anticipated results.

Approach

This study focused on potential water quality impacts and associated changes in treatment costs as a result of forest protection at Fairfax Water, Washington Aqueduct, and WSSC’s Potomac intakes. Since there is currently no acute water quality issue threatening the utilities’ ability to provide clean, safe drinking water to their customers, the focus is on potential cost impacts due to water quality deterioration and the opportunities to prevent such deterioration through forest protection.

Individual water quality and treatment chemical dose relationships were developed to inform each utility’s source water decision making. The water quality parameters considered in the water quality-treatment dose relationships were total organic carbon (TOC) and turbidity.

Overall, the study provides an initial framework that utilities can utilize to understand the benefits of forest protection activities in their source water area and how increased forest cover could bolster risk and uncertainty protections.

The specific steps of this approach included:

- Adapting the Chesapeake Bay Program Watershed Model to output TOC loading estimates,

- Developing future land cover scenarios,

- Modeling TOC, sediment, and nutrient loadings using the Watershed Model for the scenarios developed in step 2,

- Developing historic water quality-treatment dose relationships for TOC and turbidity,

- Estimating future treatments costs using modeled water quality changes from step 3 and relationships from step 4,

- Summarizing current land cover conditions,

- Identifying opportunities for forest protection,

- Reviewing forest protection considerations for source water protection planning, and

- Providing recommendations for future research and source water protection activities in the Potomac basin.

Please feel free to contact the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin with any questions.

Support and funding for the project was provided by: